When Norito Myochin disappeared, his family was unable to find closure. The forgotten keepsake of a Utah family helped heal the ‘incomprehensible wounds of war’

The year is 1968. The sea breeze tousled the sod of an Okinawa golf course. Dick Johnson stood on the fairway, 9-iron in hand, eyeing the green. The outing was a break from his high intensity work in the back of a B-52 bomber, manning the electronic defense systems while his crew flew missions to Vietnam dropping some 54,000 pounds worth of bombs on 8-square-mile strips of jungle.

Before this assignment, he flew more modern, G-model bombers, that carried nuclear weapons, though they were never used.

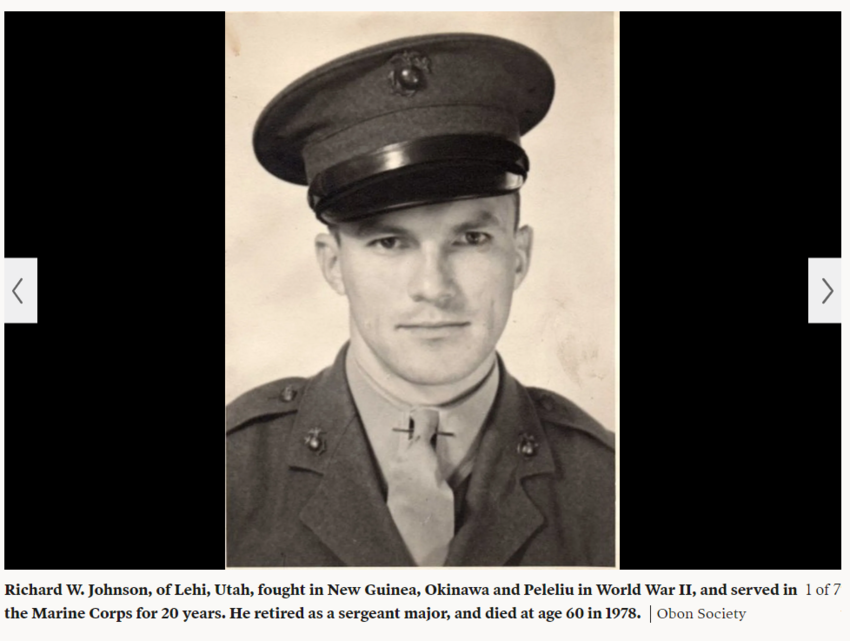

Johnson gazed at the concrete mounds bordering the golf course, originally built to fortify the island from the Allied invasion decades earlier. He imagined his father, Richard W. Johnson, landing on these same beaches in 1945, taking part in the bloodiest battle of the Pacific campaign, and the final major conflict of World War II.

It was this strange juxtaposition of fates that stayed with him, even after his service. A father and son, on the same island years apart, experiencing very different wars.

This moment on Okinawa flooded back to Johnson’s memory when his son brought him an old Japanese flag found tucked away in the family keepsakes of their Lehi home. The flag had handwritten characters circling the bright red sun in the middle.

It was as mysterious to Johnson as his father’s time spent as a Marine in the Pacific theater of World War II — a time Johnson’s father rarely talked about when he got home. In fact, Johnson only got his father to speak about the war once. And he certainly never spoke of the curious flag.

It was only when Johnson’s wife, Marlene, saw a similar flag in a magazine article, that the family began to understand what the object represented — and that it absolutely had to be returned.

War does not end with the signing of a treaty. A complex logistical process continues in earnest after the conflict. The rebuilding of infrastructure, rehabilitation of soldiers and the recovery of the dead.

After World War II, the U.S. began a massive program to bring more than 171,000 bodies home from more than 80 countries, according to historian Kim Clarke. Even today, the government continues to slowly recover the bodies of its fallen. In 2018, for example, the Trump administration successfully negotiated the release of 55 boxes of remains from North Korea, dating back to the Korean War.

In Japan, the issue of missing relatives casts a larger shadow, where many more are affected in a much smaller land mass. An estimated 2.4 million Japanese died overseas in World War II, and while numerous ministries and bureaus collaborate to repatriate remains, the bodies of nearly half are still missing.

For over 70 years, the Myochin family’s fate looked like the losing side of this coin flip. Their eldest son, Norito, volunteered to join the Japanese Imperial Navy. The eldest of 12 children, from a farm 10 miles outside Hiroshima, Norito was expected to help lead the household when he returned.

He was 22 when he was killed in action. Not a trace of him came home. Even the day of his death was unknown — records said Dec. 31, 1944, as a substitute. Heartbroken, the family grieved through the hard labor of their farm life. The next year, the world’s first atomic bomb was dropped, and Norito’s father went to help fight fires in the city’s suburbs. He died young, likely from exposure to radiation.

The large Myochin family began to fracture. The absence of Norito and his father contributed. Toshinari Myochin, the first son of the following generation, felt the heavy responsibility of his role in the family order. He spent weekends keeping the farm operating — the rest of the family had moved — while he managed a machine shop in the city during the week.

Then the Myochin family was notified of a flag, or yosegaki hinomaru.

It was the flag held by the Johnsons in Lehi, Utah. The discovery began to reunite the family under the promise of Norito’s return home. The Johnson family had mailed their flag to the Obon Society, which specialized in the collection and return of these unique artifacts, in hopes the family could be identified. Translators identified the names on the flag, tracing it back to Norito.

According to Rex Ziak, president of the Obon Society, the importance of these flags cannot be overstated. Along with that flag, he said, comes “the living spirit of that person.” So unique is this yosegaki hinomaru that their organization can “return a flag back to a family with a higher rate of accuracy than DNA can trace back a bone or a tooth.”

The Obon Society estimates there are still 50,000 similar flags in the U.S. at this time.

After seven decades, the Myochins learned that Norito died on the island of Peleliu, that this object was carefully taken and preserved by Richard Johnson for years and passed on to his children. 84-year-old Keiko Hirota, one of Norito’s two surviving sisters, was stunned by the news. She said she “couldn’t stop her tears.”

Richard reflected on the Battle of Peleliu during a recorded interview in 1977 — the only time he spoke of the war. The island reached 115 degrees during the day, and their water was tainted with oil from unwashed drums. “They told us we’d be off there in 48 hours,” Richard said. “Forty-eight days later, we were still killing those guys and they were still trying to kill us.”

Writer Eugene Sledge, in his account of the battle, wrote: “None came out unscathed. Many gave their lives, their health and some their sanity. All who survived will long remember the horror that they would rather forget.”

After the battle, craters pockmarked the coral island. Its jungle was denuded of all foliage, exposing ghostly limestone gullies and a vast network of caves. Richard would sail from that island alive, but 1,544 Americans and almost 11,000 Japanese would not. Despite the heavy toll, Peleliu would not play any significant strategic role in the rest of the war. “It’s a sad thing to realize you went through all this for a bunch of craters,” Richard said. “The whole thing was a big farce.”

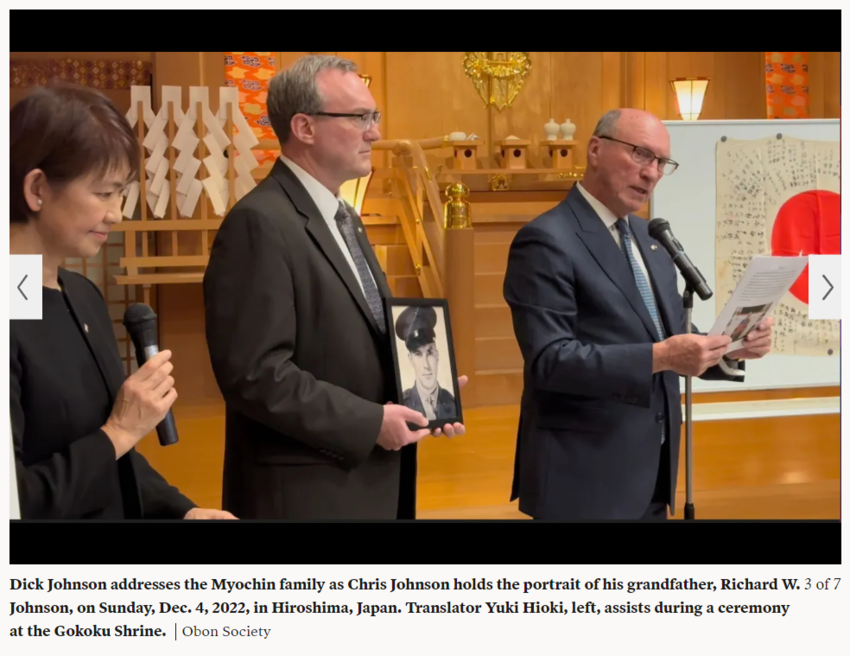

The Johnsons were initially reluctant to meet the Myochins. “Would they think my grandfather killed the man?” they wondered. “Did they harbor resentments towards us?”

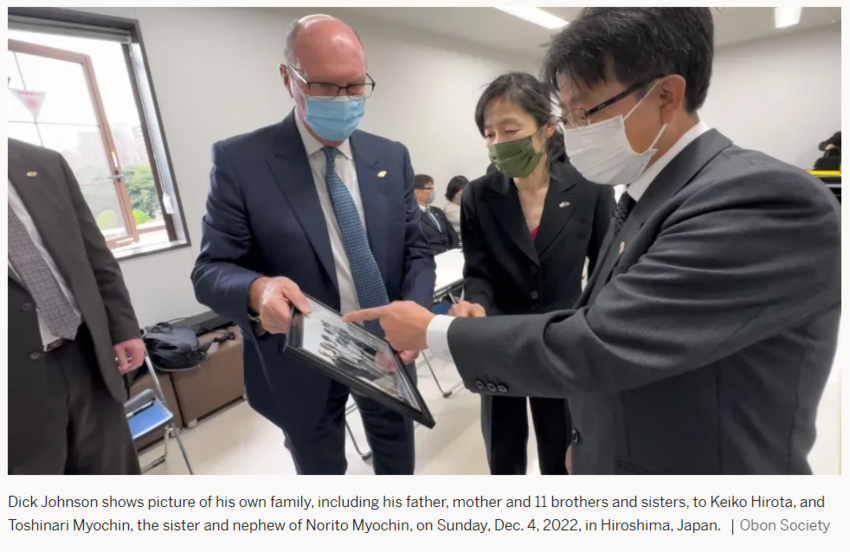

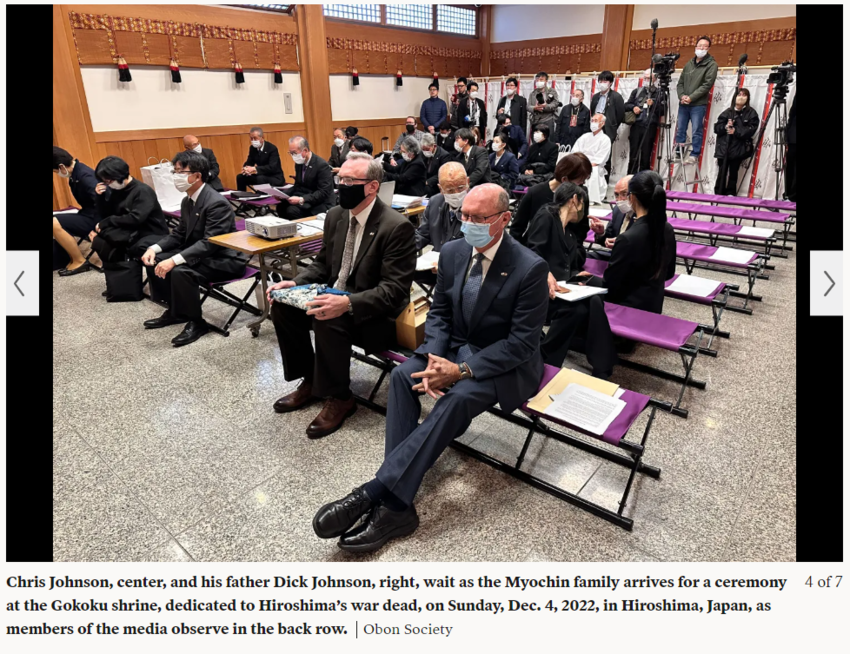

Months later, Dick Johnson and his son, Chris, sat around a table with the members of the extended Myochin family. They were “like old friends getting together for lunch,” Johnson said, “at a site where some of the most terrible things in history have happened.”

Lunch was held less than 100 yards from where the atomic bomb had been dropped in Hiroshima. Ziak said he is always amazed by this process of reconciliation. “Two modern families that have much more in common with each other than their differences,” he said, “just a magical, magical, unforgettable moment.”

“It was sobering to see the value the family placed on the flag, which was only an interesting memento for us,” Johnson said.

Remarkably, both Norito and Johnson were the eldest of 12 children. Both families also saw the sobering impact of the atomic bomb, but from vastly different vantage points. If the bomb had not been dropped, Johnson speculates that his father would likely have died fighting on the Japanese mainland. But Norito’s father died from the bomb’s effects.

Johnson ended up flying with nuclear weapons during his time in the Air Force. “It caused me to ponder about nuclear weapons. I never thought much about it,” he said. “Once I was in service, it was just what I did — it was my duty, if required, to drop nuclear weapons.”

When Keiko, Norito’s sister, was 7, she recalled seeing a brilliant bright flash from over the ridge line. Miles away, the atomic bomb had been dropped and tens of thousands were killed instantly.

“Her whole life has been tempered by (the bomb),” Ziak told me. “Who she met, who she married, what she did in her life, would have all been under the shadow of it.”

The families spent time together in Shinto shrines, the family farm and war museums. Though they spoke different languages, they managed to communicate through gifts and gestures of humility. With each passing moment, Johnson and his son grew in the belief that “even the incomprehensible wounds of war can be healed.”

Keiko tearfully held her brother’s flag at the family memorial site, among the stone markers of her parents and siblings. She got on her knees, no easy task at her age. She lit incense and said a prayer. Holding the flag in her hands, the only part of Norito to ever return, Keiko expressed only gratitude.

Her brother was home after a long, long journey.

https://www.deseret.com/2023/2/17/23583422/world-war-2-remains-returned-yosegaki-hinomaru?fbclid=IwAR0NegRG-ZSAD1oFS7gvpjLRsaw8rbygJTdEVNXVPTKfznRhlkeZ8uly_I8