The keepsake was returned to the family of a Japanese soldier who died in World War II

Toshihiro Mutsuda was making preparations for his mother’s funeral in late March when he made a miraculous discovery. His mother, Masae, had lived a long and full life. But most of those 102 years had been spent without Shigeyoshi, her husband and Mutsuda’s father, after Shigeyoshi died in the Second World War.

Shigeyoshi died in 1944 somewhere on the island of Saipan in the western Pacific Ocean, Japanese authorities told his family. His body was never recovered. Mutsuda, now 82, and his two siblings grew up with few memories of their father.

Then an acquaintance sent Mutsuda a photo. It showed a Japanese flag hanging in an American museum, covered in Japanese names written in black ink.

Mutsuda recognized those names. They were his relatives and family friends. Near the center, in a larger script, was Shigeyoshi’s name.

It felt like fate. Just as he was arranging to say goodbye to his mother, Mutsuda had discovered his father’s most treasured belonging: a Yosegaki Hinomaru flag, a keepsake Japanese soldiers carried for good luck in World War II, adorned with the names of their friends and family. He postponed the funeral, determined to reunite his family with the flag.

It was returned to Mutsuda and his siblings in a ceremony in Tokyo on Saturday, concluding an unlikely effort by a nonprofit and American and Japanese researchers to reconnect the family with a piece of their father.

“We are all so happy together finally,” Mutsuda told The Washington Post in a statement translated from Japanese.

News of Shigeyoshi’s flag only reached Mutsuda because of an offhand exchange between two historical researchers. Frank Thompson, an assistant director at the Naval History and Heritage Command, photographed the flag on a visit to the USS Lexington Museum in Corpus Christi, Tex., in February.

The USS Lexington, a World War II aircraft carrier, battled Japanese ships in the Pacific before being converted into a naval aviation museum in 1992. Its curators didn’t realize that it was now carrying a Japanese family’s treasure. Shigeyoshi’s flag had been donated to the Lexington in 1994, said Steve Banta, the museum’s executive director. There was no record of its donor.

The flag was described by the Lexington as the relic of a kamikaze pilot. Thompson sent the photo to a friend in Japan. The photo circulated between curious researchers there, who narrowed down its origin using a red seal on the flag unique to a shrine in the Gifu region. Eventually, they found the Mutsudas, who told them the museum’s label was incorrect. Shigeyoshi was drafted into the Imperial Japanese Army in 1943 and died a year later in Saipan at the age of 23, according to Thompson.

“I recognized immediately that picture of the flag was my father’s flag,” Mutsuda said. There, hung belowdecks in an American warship, was the closest remaining link to his father. But how could he get it back?

Mutsuda found someone else who understood what was at stake. Keiko Ziak saw her mother reduced to tears when her grandfather’s Yosegaki Hinomaru flag was returned to her family in 2007.

“My mother said, ‘[The] strong spirit of the grandfather really wanted to come home. So finally he came back to see us,’” Ziak recalled.

Share this articleShare

Ziak’s flag was returned to her family by a collector from Toronto. Like Mutsuda’s, it had probably been recovered as a souvenir by Allied forces and brought back across the Pacific. Ziak and her husband, Rex, said there are many more.

“This item became the most popular souvenir of the whole Pacific theater,” Rex Ziak said. “They came home by the tens of thousands.”

The Ziaks, who live in Oregon, knew what returning the flags meant to bereaved Japanese families. They formed a nonprofit, Obon Society, to take on the challenge, accepting donated flags from American collectors and poring through records to match them with the Japanese families whose names were still inked on the fabric.

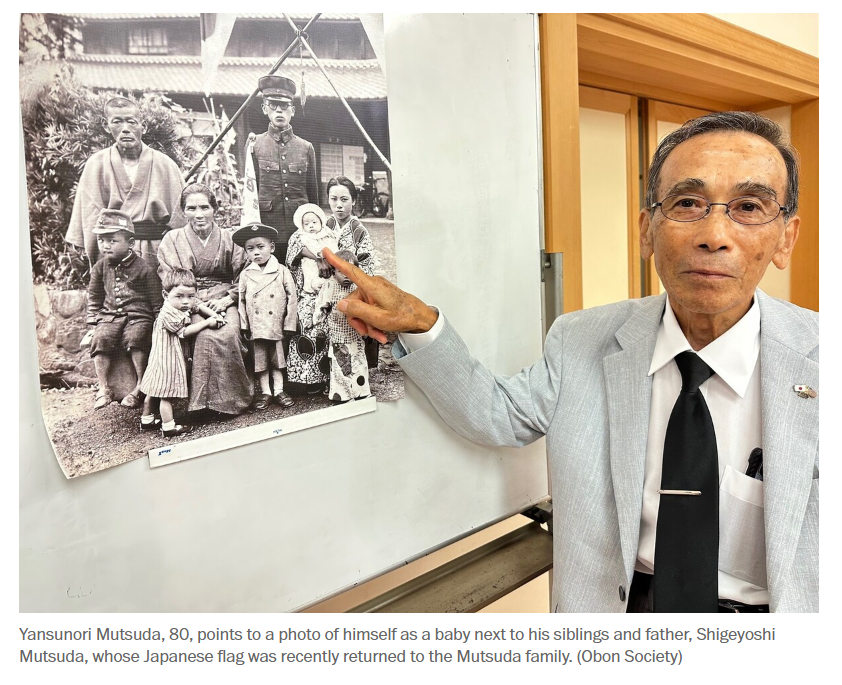

Mutsuda came to Obon Society in April with a slam-dunk case. He showed the Ziaks a black-and-white photo of his family — one where Mutsuda was only a toddler. Shigeyoshi loomed above him, carrying a flag. The writing on it matched the photo from the Lexington.

When the Ziaks contacted the museum, Banta was stunned to learn of the significance of his exhibit. But the former Navy helicopter pilot needed no convincing.

“We knew that this flag did not belong to us,” Banta said. “And we needed to return it to the family.”

The repatriation began on July 20 when staff at the Lexington removed the flag from its frame in a ceremony in the ship’s hangar bay. Banta and the Ziaks then accompanied the flag to Tokyo. On Saturday, they gathered at the Yasukuni Shrine, which honors Japanese soldiers killed in the country’s wars, to return the flag to the Mutsuda siblings.

Masae — Shigeyoshi’s wife and the Mutsuda children’s mother — had traveled to the shrine yearly to remember her husband after the war, the Mutsudas told Rex Ziak. She made the trip once more this year with her children, who brought her cremated remains in an urn so she could be with them when they received the flag.

The Ziaks said Mutsuda’s story was a highlight among the roughly 500 flags they’ve been able to return to Japanese families so far. They want to scale up their work as the 80th anniversary of the end of the war approaches, Rex Ziak added. He advocated for a wider effort to return flags, with support from the U.S. government.

“Here’s an opportunity for America to reach out and touch these families, one by one, by returning the remains of their missing relatives,” Rex Ziak said. “It would be one of the most spectacular humanitarian gestures the world has ever seen.”

Mutsuda added that the repatriation was a heartening gesture of cooperation between American and Japanese organizations — and a reconciliation that his parents would have been glad to see.

“[Shigeyoshi’s] flag made us feel that my father and mother wanted to tell us, ‘Please do not repeat this horrible and painful experience [that] we had been through ever again,’” he said.

After the ceremony, the group joined Mutsuda and his siblings in a private room for lunch. Before they sat down with their bento boxes, the Mutsudas arranged their mother’s urn and their father’s flag next to each other on a shelf and bowed to pray.

Mutsuda imagined his parents deep in conversation, finally able to catch up on almost 80 years’ worth of stories together.

“We want to let both my parents [get] acquainted together as long as they want,” Mutsuda said. “Then when they are ready, we will put my mother’s ash into the temple in Kyoto for her departure to heaven to be with her husband forever.”

https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2023/08/04/wwii-japanese-flag-returned-lexington/?fbclid=IwAR1WHuHW8kSIOvU-PTkK1g4caQcxSQc63uRn1tMCvgUwjqwccRp5am0FfY0